|

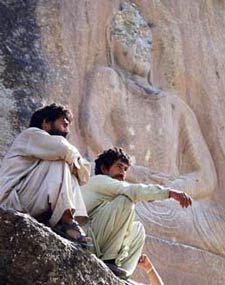

Stone Carving - Taxila - Pakistan

Swat Valley - once upon a time Buddha's Garden in Pakistan. The gloomy supplement at the end of this travelogue makes it clear that recent changes can bring disaster beyond imagination. Even in paradise evel is lurking just behind the corner.

Keep Peshawar green warns the signboard at a central junction in the capital of Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province. Yet motorized rickshaws hum around and spit the bluish smoke from their two-stroke engines over the asphalt. Peshawar's predominant colours are brown and grey. The whole inner town is a labyrinth of backstreets and alleys with all the charm of an overcrowded oriental bazaar. The smell of ancient times, when travellers on horseback and merchants leading camel caravans entered the town gates, is still there in the dark interiors of the traditional teahouses along Qissa Kahani, the Street of Storytellers.

Peshawar - Storytellers Street in the old inner town

Clouds of dust whirl around the walls of the Bala Hissar Fortress at the edge of the old city. Peshawar is only 30 miles away from the Khyber Pass and the Afghan border. The region is flooded with camps where Afghan refugees are engaged in doubtful activities, mainly arms smuggling and drugs dealing. Capital of terrorism is the new nickname that has ruined the reputation of Peshawar. But in its own polluted way it is still a place for all seasons.

A Buddhist Holy Land

In the 4th century BC Alexander the Great subdued the Persian empire, he crossed the Hindu Kush Range and invaded the Indian subcontinent. His Macedonian warriors conquered Taxila in the land of Gandhara, the ancient name of the Peshawar plain. Taxila was already in those days a renowned centre of learning. Alexander returned home, but he left his heritage, the splendour of Greek civilization. In the same period Buddhism spread over the land and found a fertile soil in Gandhara, where the ruler Ashoka converted to the new religion and embraced a policy of tolerance. The high cultural level was maintained for many centuries in Taxila. Pilgrims from China and India came to this Holy Land of Buddhism.

Taxila site - ancient crossroads of civilizations

Nowadays Taxila, about 80 miles east of Peshawar, is a famous archaeological site. Buddhist stupas, some of huge proportions, mark the landscape together with the remnants of Greek temples. The local museum preserves the treasures of Gandhara. Magnificent statues in stucco or limestone show the Great Buddha with a peaceful smile on his oriental face, but also dressed and humanized in the style of the classical Greek sculptures. Even today Taxila strikes the visitor as a unique site, where East and West once met and mingled.

Churchill Picket

Takht-i-Bahi is another Buddhist sanctuary in the hills north of Peshawar. The ruins of the ancient monastery are spread over the higher slopes. The crumbled walls of the central courtyard surround a stone forest of stupas; the cells for the monks are dark caves. Suddenly thin sounds break through the silence. A boy plays the flute on a hilltop, the faint melody starts echoing towards the jagged ridge of distant mountains. The boy belongs to the Pathan village close to Takht-i-Bahi. It is a typical settlement, with clay walls surrounding the fortified farmhouses of each family. The Pathans live in the harsh mountains of Pakistan and Afghanistan. These belligerent Muslim tribes were tough adversaries for the British. Only at the end of the 19th century British troops could penetrate the homeland of the Pathans and impose to some extent their colonial law and order.

Takht-i-Bahi - Buddhist sanctuary in northern Pakistan

Today I am only hindered by counter-traffic, mainly multi-coloured trucks, glittering all over like moving signboards, while I am heading for the top of the Malakand Pass. One century ago the British garrison had a narrow escape here when it was attacked by fierce Pathan warriors who had declared Holy War on the infidels. The whole campaign was covered in the British press by the young war-correspondent Winston Churchill. On the other side of the Malakand Pass a watch-tower on a hill remembers his presence: white-painted characters on the rock form the name Churchill Picket. I take a break in the nearest resthouse of the Pakistan Tourist Development Corporation. Churchill Picket is darkened by black clouds. Heavy showers pour down, sweeping the foamy waters of Swat River over the pebbled creeks at the banks.

Along Swat River

The Swat River basin has shaped this valley, north to south some hundred km long. Lower Swat in the south was once known as Uddyana, the garden. Buddhism was the dominant religion of the original population till the Pathans penetrated the region centuries ago and forced the Swatis to convert to Islam. Yet Buddhist past has left its marks. In the southern capital of Swat, the twin-towns of Saidu Sharif and Mingora, the Swat Museum, recently reorganized with Japanese funds, boasts its fine collection of Gandhara art. Near Mingora a small road winds towards White Palace. The residence of the Wali, the former ruler of Swat, has been transformed into a first class hotel for those who want to combine luxury with the magnificent scenery of the dark green hills all around. The Wali's benevolent autocracy lasted till 1969, when Swat was finally incorporated into the Pakistan state.

White-bearded village malik welcomes foreign visitors in Jehanabad

Jehanabad Buddha, north of Mingora, is a marvellous work of art. In the 7th century this gigantic sitting Buddha was carved on the steep rockface of a long and winding gorge. One had to cross a swaying foot-bridge of wooden slats and rope cables till a few years ago, but now it is replaced by a concrete one. Modern times travel fast. At Jehanabad village I am welcomed by a white-bearded malik, the local senior. Youngsters guide me through the village, where veiled women hide in doorways. The Buddha smiles from above when I take a rest at his feet. Just a few years ago Muslim extremists covered his face with black paint. Restoring the serene smile of the Buddha has costed a lot. The malik approves of the clean-up. Bad for religion, he twinkles, but good for tourism. Asalam aleikum, peace be with us all.

Trouble in Upper Swat

In Upper Swat the valley gets narrower. Rocky slopes run sky-high. A silvery green curtain of eucalyptus trees and white poplars lines the riverside; their leaves rustle in the breeze while spring blows its way through the valley. Upper Swat is the dwelling-place of Kohistanis or People of the Mountains, who stick to their own language and traditional customs.

In the village of Bahrain the Swat River has turned into a roaring torrent. Women have completely disappeared here and only grim looking Kohistanis are strolling along, wrapped up in grey woolen blankets. Bahrain has a small bazaar where Swat handicraft is sold. I buy a Koran book-rest and I touch semi-precious stones, the dark blue of lapis lazuli, the milky white of moonstone. I admire the fine cloth with its embroidery and ornaments of mirror glass, that brightens up the dress of the invisible local women. More to the north real adventure awaits at Kalam, the starting-point for trekking in the heavily forested Alpine area, where local Kohistanis are engaged in tribal feuds. According to an audacious Lonely Planet traveller 'the hills echoed in Kalam with distincly un-playful automatic gunfire through the night...'

Valley of Happiness

Promoted in the Golden Sixties as the Switzerland of the East, Swat used to be a temporary refuge for hippies and an obligatory stop on their trail to Nepal. I head for the resort of Miandam at the end of an unpolluted side-valley. The PTDC Motel above the village consists of white bungalows amidst green lawns. From the spacious terrace one is dazzled by the unparalleled view: the whole valley is speckled with Pathan hamlets and striped in the vivid colours of terraced plots where wheat and other crops are grown. In the background, all around the pinewoods on the hilltops, the snow-capped, up to 6000 metres high peaks of Kohistan glance in bright sunlight.

Pathan boys on the mountain slopes above the village of Miandam

Paradise can hardly offer greater scenery. I take a four hours' walk, following muddy tracks at the edge of breath-taking precipices and touching at last the melting snow. On my way back I am cordially greeted by a Pathan ploughman who offers me a bowl of buffalo milk from his own stock. Any foreigner on his property is a guest and should be welcomed with a gift. Later on, in Miandam village, I meet Mohammad Khan Painda, writer and owner of the local handicraft shop. He shows me the age-old stone tablet he has dug up somewhere close by. It represents Buddha between two enlightened souls or Bodhisattvas.

The manager of the PTDC Motel fancies other goods, Italian sun-glasses. I should bring them along next time. And I am bound to come back one day, he says, since I have planted a twig of a white poplar in the garden of his motel. Swat will probably have changed a lot by then, with some Swatis looking through western sun-glasses and others narrowing their vision by exclusive Koran reading. I promise to look out for the glasses. In the name of Allah, Buddha and the whole divine natural beauty of this remote Eden in the northern mountains of Pakistan.

Paradise Lost

Ten years later, at the dawn of the 21th century, travelling freely in Swat belongs to the past. Landscape still embedded in its wild beauty - people on the run, embedded in terror. These days Swat Valley is a lost paradise, turned into Taliban playground.

IRIN Humanitarian News and Pakistani academic Adil Najam report about the situation.

Northern Pakistan - Taliban militants on guard in Swat Valley

Times have changed in Swat. The radical Islamic leader Sufi Mohammad urged the Pashtun or Pathan population of Swat to establish Islamic law, Sharia, in the region. When he was jailed in 2002, his son-in-law Fazlullah took over and aligned himself with the Pakistan Taliban. Fazalullah, nicknamed Radio Mullah set up an illegal radio network in Swat and used it to preach Holy War against all infidels who violated the Pashtunwali, the Pathans’ traditional and strictly Islamic way of life. Since the summer of 2007 the Pakistan army has been fighting in Swat against the Islamic militants led by Fazlullah. A major part of the population of Swat has fled the violence and refugee camps have been set up in Mingora, the main town of Swat.

Following the example of his Taliban friends in Afghanistan, Fazlullah wants to abolish education for girls. Up to two hundred girls’ schools in Swat have already been destroyed by fire or bombing. Fazlullah’s Taliban miltants have been reported responsible for beheadings, public floggings and executions without trial. Swat inhabitants who stood up against the militants have been forced out of the valley. Video and music shops have been burnt or forcibly closed down. Women have also been ordered via militant-run radio stations to give up work and stay at home. Men have been ordered to grow beards and wear Islamic prayer caps.

In February 2009 the Pakistan government of the North West Frontier Province, to which Swat belongs, has agreed a truce with the Islamic extremists. Many residents have welcomed the ceasefire, but the deal with the Taliban militants has got its price – Islamic law of Sharia will be imposed in Swat. Fazlullah’s militants have promised to allow lower education for girls and Pakistan government wants to re-open all schools in Swat. Few girls however attend school despite the truce. And if they do, they must be fully veiled, as ordered by the militants.

Jehanabad Buddha defaced

In September militants detonated explosives placed above and below the Buddha, but only damaged the stone rather than the sculpture. According to a police chief it appeared ‘to be the work of the local militants who condemn these relics as being un-Islamic.’

A curator at the Swat Museum, known for its collection of Gandhara sculptures, said that ‘Islam teaches us to respect other religions and faiths, but unfortunately some elements are disturbing the peace in the Swat Valley.’ The destruction of the Jehanabad Buddha is on the direct call from extremist mullah Fazlullah who has been spreading his message of hate and violence across the region. [Sources: IRIN Humanitarian News & Pakistani academic Adil Najam]

I wonder if the manager of the Miandam Motel in Swat still wants the Italian sun-glasses he asked me to bring along the next time I would visit the place. Hard to tell and anyway, there most probably will not be a next time.

Text - A Thiry

|

Homeland

Homeland  East of Eden

East of Eden  Buddha in Pakistan

Buddha in Pakistan

Homeland

Homeland  East of Eden

East of Eden  Buddha in Pakistan

Buddha in Pakistan