|

Border Region

Assyrian stele close to Hassana (G.Bell 1909)

Until the First World War the Assyrian mountaineers under the leadership of their patriarch Mar Shimun formed an Ottoman millet in the Hakkari mountain range. They were semi-independent ashiret-people, subdivided into the Assyrian tribes of Tiyari, Tkhoma, Baz, Dez, Tal and Jelu. The Hasnaye never had such a status, they were tributary raya-people, dependent on the goodwill of the Kurdish landowners or aghas of Shirnak, who collected taxes and counted on the Hasnaye for forced labour. Though living in the foothills of Mount Judi, the Hasnaye considered themselves Bohtanis, people of the Lower Bohtan plain close to the rivers Tigris and Khabur.

Mount Judi

The name Judi is a corrupt Arabic adaptation of the Greek denomination Gordyae, which on its turn is derived from the Chaldo-Aramaic Qardu. According to Mesopotamian tradition Noah’s Ark stranded on the top of Mount Judi. This version is mentioned in the Koran as well as in the Jewish Targum. The Christian Bible - or Peshito in Syriac - describes an alternative location: in Genesis 8, 4-5 the Ark got stuck on the mountains of Ararat. The Ararat however is an isolated mountain north of Lake Van in old Armenia, where the ancient kingdom of Urartu was situated. In the 9th and 8th century BC the Assyrians of Nineveh were at war with the Urartians, who expanded their territory towards Mesopotamia. From the Assyrian point of view, the biblical expression mountains of Ararat gets its full plural meaning as mountains of Urartu. The biblical Genesis had its Jewish-Babylonian origin in the Mesopotamian plain and seen from there, Judi is definitely the first and most striking northern mountain ridge. It was to that sacred location that Mesopotamian Muslims, Jews and Christians went on pilgrimage (1).

The detailed map from the British War Office, dated 1916, confirms the holiness of the location: the top of Judi, 2.114 meter (2) above sea level, is marked there with the indication Ziaret, the Arabic denomination for sanctuary. Grandpa Rasho, the patriarch of the Assyrian Dirlik family in the old town centre of Mechelen, has often climbed to the top when he was a young man in Hassana. He even makes claims of having seen big rusty nails there, belonging according to him to the remnants of the Ark.

Popular tradition is strengthened by more scientific arguments, connected with the etymology of place-names around Judi. Arabic sources from the 10th century mention a village called Thamanin, built by Noah at the foot of Mount Judi. This Semitic name may refer to the number 8, i.e. the eight persons who according to Genesis came out of the Ark: Noah, his wife and their three sons with their wives (3). As an equivalent of Thamanin the name Heshtane originated, hesht being the Kurdish word for 8. Arabic 10th century geography located Thamanin south of Mount Judi, on the river Hezil and close to Zakho on the Khabur. Zakho however was known to these early Arabic geographers as Hasaniyeh (4). So, it looks as if that ancient name for Zakho was later on transmitted to the most important Christian village on the southern slope of Mount Judi, so that Hassana till today has preserved in its etymology the age-old biblical link with Genesis and Noah’s Ark. Furthermore the name of the Christian village of Bespin to the east can be explained as House of the Boat. And just above Hassana there is still a lush oasis, called Zehwe, with ancient ruins close by; according to local tradition there once stood the so called Abi Abiun monastery with Noah’s grave.

Ukmel - ruins of Deir Kemol (G Segers 2004)

Seven Fathers When was Hassana founded? The Hasnaye generally believe that through the centuries the village came down from Tura, i.e. the Mountain, the common Sureth-name in Hassana for Mount Judi. This again might be a reminiscence of early Christian settlement on Upper Judi. On the other hand the Hasnaye have preserved a common story about the foundation of Hassana: the legend of the Seven Fathers. Centuries ago the mighty ruler Hassan Bey controlled the Judi region. Assyrian Christians, Nasturnaye or Nestorians, emigrated from Van and Hakkari and wanted to settle down on the land of Hassan Bey. They negotiated with his successors, they were granted permission to found their own Christian village and called it Hassana or Hassanbey, i.e. Hassan’s place. Dubious as this explanation may be, it suggests that these Christian pioneers had to accept foreign authority, and this corresponds with historical reality: as raya-people the Hasnaye were always left to the tender mercies of Kurdish aghas from Shirnak.

The Seven Fathers or clan leaders, who had found a new home on Lower Judi, divided their territory and in this way the family areas of Hassana were shaped and the family farmlands demarcated. In Mechelen the Hasnaye go by their official Turkish surnames, like Alagas, Begtas, Diril, Dirlik, Duru, Eksen, Eke, Kucam, Kulan, Kürüm, Salcuk and others, but for internal use they still stick to the old clan names, derived from the Seven Fathers. The traditional denominations that are most frequently mentioned are these: Babehur, Gulu, Keretu, Kerru, Nishana Shimun, Shana, Zengil and Zehru. The original meaning of some of them - Babehur means Little Father and Kerru means Deaf One - indicates that they go back to the nicknames of the legendary Founding Fathers.

Reverend Mattai, now living in Holland (Wierden) (6), was the Protestant minister of Hassana and he is still the spiritual leader of the influential Kerru-clan. In the course of a conversation I once heard him explain that Melkan’s Zengil-clan didn’t originate from the Seven Fathers. That clan came later, he said, and perhaps zengil-zengil just imitated the sound of little bells, so that the founding ancestor of the Zengil-clan had to be a goat herder - a not so innocent joke since shepherds were poor people and Kurds were often hired to herd the flocks. The Hasnaye were a farming people and the social position of each family was largely dependent on the amount of fertile soil it cultivated. Therefore, every clan in Hassana would want to trace its origin back to the Founding fathers. The legend of the Seven Fathers functioned in this way as a kind of traditional rural framework: it provided an historical justification for the distribution of the land among the Hasnaye.

Reverend Mattai  Memorial tablet Protestant church Hassana

Reverend Mattai’s story is confirmed in an historical survey, published by the Presbyterian Center for Mission Studies. Here the travelling missionary who brought Protestantism to Hassana is identified as Samuel Audley Rhea: 'On one of his tours, he had made a visit to this place and was much drawn to its young bishop, Yosip (...) The bishop was converted and decided to go back with Mr. Rhea to Urumia to take the course of study and return as a preacher to his village. At his death, his brother, Kasha Elea, took his place and was pastor (…) in Hassan. He, too, was a good man, one of many preachers massacred by the Turks in 1895-6. Hassan was fortunate in that its Kurdish sheikh, the Agha of Shernakh, had always been very friendly to the Christians.' (9)

According to Reverend Mattai, Qasha Yusup (Yosip) died in 1885 and his brother Iliya (Elea) succeeded him. Meanwhile another missionary, Reverend Mc Dowell, had arrived in the village. Thanks to him two young converts from Hassana, a boy and a girl, could finish their theological studies at the American Mission in Urmia. The girl was called Hatun and the boy’s name was Mattai. When they returned to Hassana, this Mattai, Reverend Mattai’s grandfather, became the new Protestant minister. Hatun obtained from the American Urmia Mission the means to open a madrasa or bible-school and she started teaching in Sureth as the first female malpanata or catechist in the village.

Reverend Mattai also recalls a legendary event that took place around 1900, when the Protestant missionary Mc Dowell, of Canadian origin, visited Hassana. He suggested that the Hasnaye should emigrate to Canada and rebuild the village there under his supervision. It was a tempting proposal, but Qasha Mattai turned it down. ‘We cannot leave,’ he said. ‘Our dead are buried here, this is the sacred land of our forefathers.’

Gertrude Bell in Hassana

In the beginning of the 20th century a famous Briton, a female scholar and traveller, put Hassana on the map. Her name is Gertrude Bell (1868-1926). She studied history at Oxford and investigated archaeological sites in the Middle-East. After the First World War she played an active role in the creation of the state of Iraq under British mandate. In the spring of 1909 Gertrude Bell travelled from Baghdad to northern Mesopotamia. She stayed four days in the Judi area, May 11 to 14. She took photographs and wrote about Hassana in two letters and in three annotations in her diaries.

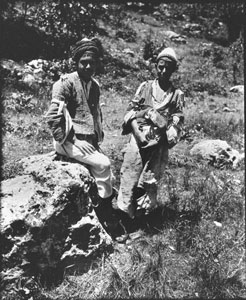

Hassana - Assyrian boys (G Bell 1909)

The next day Bell, guided by Qasha Mattai and his brother Shimun, explored the higher slopes of Mount Judi and she saw the ruined monastery at Ukmel (Deir Kemol) with a large garden of fruit trees around it. In the early morning of May 13 she climbed together with Qasha Mattai and Shimun to the top of Mount Judi to see what was left of Noah’s Ark. On the top she discovered a ruined sanctuary. She wrote: 'We got up to the Ark and it was a most wonderful place from which you could see the whole world, though I must confess there isn't much of the Ark left. We stayed there many hours, lunched and slept and looked at the view and breathed the delicious cold air.' (11) On the way down Qasha Mattai told her again of his troubles. How the Kurds came over the mountain pass and made him feed them and took everything down to his bed and his coat. How these Kurdish aghas from Shirnak always claimed this kind of ‘hospitality’ from their Christian subjects, how they levied high taxes and every now and then descended on Hassana to plunder, burn and kill (12).

The following day, when she took leave of Qasha Mattai, he gave her roses, some figs and a pomegranate. It was a final farewell. Qasha Mattai expected better living conditions from the new Turkish government. He was wrong: worse was to come.

The 1915 Massacre At the outbreak of World War I, Turkey had allied with Austria and Germany against Great Britain, France and Russia. The Year of the Armenian Genocide, 1915, was just as disastrous for the Assyrians in SE Turkey. In the summer of 1915 Turkish troops, supported by irregular Kurdish units, chased the Assyrian-Nestorian tribes out of Hakkari and in the same period the Lower Bohtan was sacked.

Hassana was attacked and burnt down. The aggressors, mainly Kurdish riffraff, murdered and plundered. They abducted the boys, girls and young women who fell into their hands, and kept them for slave labour in Kurdish households. Hassana emptied of its people. Conditions improved a bit when the aghas of Shirnak realized that they might lose their best subjects, the Christians of Hassana. According to oral tradition, the chief agha of Shirnak even announced that whoever killed one more of his Christian subjects, acted as if that person had killed the agha’s own son. At the agha’s command the remaining Hasnaye were rounded up at a place called Dadar, on the plain just to the south of Hassana. They stayed there in tents and later on they were allowed to rebuild their devastated village.

Melkan recalls what happened to his own family. His great-grandfather Zacharias possessed large gardens and fields. During the great massacre Zacharias perished with his whole family. Just one boy was saved, namely Melko. Later on the agha of Shirnak sent for him and made him stay for years in his own house. Melko, being the sole legal heir of a wealthy Christian family, became the agha’s foster son and since he was still a minor, the agha leased out his newly acquired lands to his own relative in Silopi. To this day, the present successor of this agha from Silopi occupies the lands of Melkan’s ancestor.

Mount Judi - Qasha Mattai in center (G Bell 1909)

His heroic end is also recorded in a letter dated March 6, 1916 written by Rev E W Mc Dowell (13): 'There was a general massacre in the Bohtan region (…) Among those slain were Kasha Mattai, pastor of the church in Hassan (…) The women and children who escaped death were carried away captive (…) The wife and two daughters of Muallin Mousa, the daughters of Kasha Elia, and rabi Hatoun, our Bible-Woman, were all schoolgirls in Urmia or Mardin. Kasha Mattai was killed by Kurds in the mountains while fleeing (…) The terrible feature about it was that, after the first slaughter, there were Kurds who tried to save some of the Christians alive, but the Government would not permit it. My informant had found refuge with an agha and was working for him, when a messenger from the Government came with orders to the Kurds to complete the work or be punished.'

Rev Mc Dowell made it clear that the Turkish authorities were guilty of the general massacre: they organized it and saw to it that the dirty work was completed by the Kurds. As for Gertrude Bell: Would she ever have remembered Qasha Mattai, the hospitable priest who guided her to Noah’s Ark and offered her roses from the gardens of Hassana?

NOTES

1. See Gertrude Bell, Amurath to Amurath (London, 1911), 292: ‘There was once a famous Nestorian monastery, the Cloister of the Ark, upon the summit of Mount Judi (…) Upon its ruins (…) the Moslems had erected a shrine, and this too has fallen; but Christian, Moslem and Jew still visit the mount upon a certain day in the summer and offer their obligations to the Prophet Noah.’ Also confirmed by W A Wigram, The Cradle of Mankind (London, 1922), 335: there was a truce of God on September 14; all faiths went on pilgrimage to Noah’s Ark and brought a sacrifice.

2. 8.260 feet or about 2.700 meter confer the 1916 British War Office map.

3. See also G P Badger, The Nestorians and their Rituals (London, 1852), 69: ‘Our road today (Nov. 5, 1842) lay at the foot of the high mountains of Joodi, the Tooré Kardo of the Syrians, (…) the spot on which the ark rested after the deluge. This tradition is also handed down in the name of a village in the mountains, called the Market of the Eight, with reference to the number of Noah’s family who were preserved from the flood.’

4. G. Bell, Amurath to Amurath, 287.

5. J C J Sanders, Assyro-Chaldese Christenen in Oost-Turkije en Iran (Brediusstichting, 1997), 56-57. English translation: Assyro-Chaldean Christians in East Turkey and Iran.

6. Rev. Mattai emigrated from Hassana in 1991.

7. Asahel Grant, The Nestorians or the lost tribes (London, 1841).

8. In the last chapter (‘The Last Ark’) of his book Dervish (London, 1996) travelogue writer Tim Kelsey mentions another founding date for this Protestant church: 1873.

9. Robert Blincoe, Ethnic Realities and the Church: Lessons from Kurdistan (Pasadena, Presbyterian Center for Mission Studies, 1998), 91. In o.c. also (p. 90): ‘The year on the church seal that I saw in Hassana is 1833.’

10. Gertrude Bell Archive, Univ.of Newcastle u/T Library, The Diaries, 11/5/1909.

11. G. Bell Archive, The Letters, 14 May 1909.

12. G. Bell Archive, The Diaries, 13/5/1909.

13. Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire 1915-16, Documents presented by Viscount Bryce, Doc. 41: The Nestorians of the Bohtan District, London, 1916.

|

Mechelen on Tigris

Mechelen on Tigris  The Shade of the Ark

The Shade of the Ark

Mechelen on Tigris

Mechelen on Tigris  The Shade of the Ark

The Shade of the Ark