|

In the Syrian town of Aleppo the language of Christ is heard. Not far away there are dead cities and the site where a great saint took refuge on his pillar. This is a travel report at the dawn of the new century, with the collaboration of the Syrian-Orthodox Christians of Aleppo. August Thiry

Old Aleppo

The rivalry between the two biggest town in Syria has been going on for many centuries. The capital Damascus and the northern town Aleppo both claim the title of most ancient permanently inhabited place on earth. In spite of the historical dispute a modern highway reduces the distance to three times nothing. The comfortable pullman bus covers the 350 kilometers from Damascus to Aleppo in a few hours.

Zakariyeh Mosque

The Aleppo souqs are famous, they are considered the best preserved ones in the whole Levant. Hic et nunc however they offer a desolate outlook. The overcrowded oriental flavour of the bazaar is completely gone and I am walking all alone along the narrow vaulted corridors of a dark labyrinth. In a side alley I notice a flickering light. It comes from the window of a jeweller’s shop.

Just look, not buy, says the shopkeeper when I pause for a moment in front of the glittering wealth. He appears to be Armenian, like all jewellers in Aleppo. On my way back to the main exit of the souqs I listen to the echo of my own steps in the hollow darkness behind me and a bit farther away I hear the sudden noise of a metal shutter rattling down. No prayer time for the Armenian jeweller, just closing time as the last possible buyer has left.

The Beit Wakil Hotel is a top class place in Old Aleppo. The manager shows me around. The Beit Wakil is a carefully restored merchant’s residence from the 16th century. The guestrooms at the gallery on the first floor offer a splendid view on the inner courtyard with its multicoloured paving tiles, its romantic fountain and its tangerine trees. Beit wakil was a Christian home. It once belonged to a rich Armenian family of merchants, the manager explains in a fluent combination of French and English. These original owners were living in a secluded Garden of Eden. ‘Clever behaviour,’ says the manager handing over his business card. ‘Not wise to show your Christian wealth when your neighbour is a poor Muslim.’

Almost one fifth of the population of Aleppo is Armenian. Many of them are descendants of refugees during the First World War. In 1915 the Turkish military regime, suspecting the Armenians of collaborating with the Russian invaders, ordered the massive evacuation of the Armenian population from eastern Turkey. Turkish jandarma’s and Kurds, who escorted the human convoys, brought about a massacre. More than one million Armenian citizens, among them a great number of old people, women and children, perished during the deportations towards the Syrian desert. These crimes against the Armenians are considered the first genocide of the twentieth century, though till today Turkey refuses to plead guilty and prefers to put the blame on the general tragedy of war. Collateral damage on a larger scale – as it would be called now. Armenian survivors found some kind of refuge in Aleppo. Many of them stayed and started up again from scratch, using their traditional talents for trade and craftsmanship. Their presence in Old Aleppo can hardly be overlooked: the signboards of the jewelry shops are often bilingual, Arabic and Armenian.

The Language of Christ

Syrian-Orthodox Mass Aleppo

The Syrian-Orthodox Christians call themselves descendants of the old Arameans. These Semitic tribes were wandering over the plains of Mesopotamia between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates three thousand years ago and later on their language became the lingua franca of the entire Middle East. Also in Palestine, where in the days of Christ an Aramaic dialect was spoken.

Till today the Syrian-Orthodox Church has preserved an ancient form of Aramaic, Old Syriac, in its religious services. ‘Our traditions are our survival and our strength,’ says Qasha Kaplo. ‘Our young ones who want to emigrate do not realize enough that living in Europe or America means isolation from the source of Christian faith and psychological mutilation.’ He glances at Yoseph.

My young guide is born in the Jezireh-district, in the north-eastern part of the Syrian desert. After World War I Christian families from Turkey started up new settlements here and cultivated the area. Growing crops along irrigation channels in remote villages was not the kind of future Yoseph desired for himself. His parents allowed him to study at the university of Aleppo. He doesn’t want to go back to his place of birth and he is trying hard to get a grant from a British university. ‘Any university will do,’ says Yoseph, ‘and perhaps Great Britain is just a bad dream, but still, it is the only one I have left these days.’

There are many churches in the neighbourhood of Suleimaniyeh Street. They preach the Greek-Orthodox faith and that of the so-called monophysites or Armenian-Orthodox and Syrian-Orthodox Christians, who believe in the one divine nature of Christ. Some centuries ago other Christian communities, like the Maronites and the Chaldeans, went their own way and reunited with Catholic Rome. All these Christians have their own metropolitans and their own churches; a Babylonian mixture of Christianity in the old centre of predominantly Islamic Aleppo. Their church buildings have nevertheless been restored and embellished in recent times, also thanks to the gifts of Christian emigrants with nostalgic feelings and a bad conscience. Furthermore, the Syrian government forbids public discrimination of ethnic and religious minorities. And what is even more important: Christian churches are by the goodwill of the Syrian state exempted from paying taxes.

Crusaders

‘Damascus?’ sneers Yoseph in the minibus that takes us in southern direction along the highway. ‘Damascus? Nothing good comes from there. That is where the bastards of Tamerlane live.’ At the end of the fourteenth century the bloodthirsty Mongolian conqueror Tamerlane, or Timur the Lame from Samarkand, marched from Central Asia to the Middle East. Although he himself was a fanatic Muslim, he put without mercy the Islamic population of the conquered territories to the sword. There was one God, Allah, in heaven, he declared, and one ruler on earth: Tamerlane. His fierce horsemen destroyed Damascus and those who survived the massacre were carried away as slaves under the Mongolian yoke. So, the decendants of these slaves became Tamerlane’s bastards. At least according to the people of Aleppo, who were saved from his wrath.

History sometimes repeats itself in strange ways. We are heading towards the city of Hama, a place of ill fame. President Hafez al-Assad, leading the Arabian-Nationalist Baath Party, stayed in power in Syria for thirty years, till his death in 2000. He had all the key positions in the country occupied by his fellow believers and tribal kinsmen, the Alevits, in fact an Islamic minority sect of Shiites. In the early eighties of the last century Hama was a hotbed of Muslim fundamentalists who were secretly preparing a revolt. President Assad made his move without hesitation. He sent the army and Hama was bombarded, which resulted into thousands of victims. From then onwards it was all over and out with the fundamentalist Islamic Brotherhood in Syria.

‘There is nothing left from that period,’ says Yoseph. ‘Today it is all concrete, new housing estates, and dust.’ There were enough survivors however to make a fresh start in Hama. That was hardly the case in Ma’arat, a smaller place we pass on our way. It was the scene of one of the most gruesome episodes during the First Crusade. The Crusaders had large bands of plunderers in their trail. They ran out of food and they besieged the small Muslim town of Ma’arat in the year 1099. The town surrendered and the starving Christian warriors seized the Muslims of Ma’arat. They were slaughtered, their dead bodies were cut to pieces and fried on big fires to still the Crusaders’ hunger. Yoseph can hardly believe it when I tell him the true story. How could this happen? The Crusaders were above all the defenders of Christiantity, the liberators of the Holy Places from Islam. So he argues. I tell him that in Islamic eyes the Crusades were just the unholy wars of the despised Christian dogs. ‘Of course,’ he concludes, ‘they have always hated us like hell.’

Dead Cities

We leave the main road and turn off into a mountainous region that stretches west of Aleppo towards the Turkish border. This is the area of the dead cities: deserted ruins, Byzantine ghost town in a bleak landscape covered with rocks and thorny bushes.

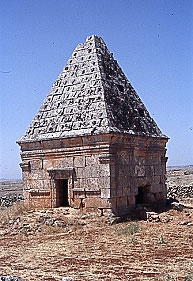

Sergilla

Sergilla is just one of these Byzantine-Christian settlements, gradually deserted by their inhabitants after the fifth century AD. Overpopulation, earthquakes, poor harvests, lasting aridity, the general feeling of unsafety due to the expanding Islam – probably a combination of all this caused the decay. What was left of these once flourishing cities remained on the spot; mainly because the whole area got permanently depopulated, without new settlements that could use the old stones as building material.

We move on. It is a long drive off the beaten tracks to the hamlet of Qalb Loze, which is now inhabited by a few Muslim families. In this remote place the dark yellow stone walls of a church from the fifth century are still standing upright. Some children are playing in the semicircular front part where the sanctuary used to be, and the plain blue sky above replaces the roof and the long gone cupola. Men with baggy trousers and red and white scarves on their heads push forward and swarm around us when we are about to leave. Yoseph answers to their questions. They nod and smile and pronounce the only English words they know: Wilkom, wilkom!

Qalb Loze is as far as we go. On the way back we get a glimpse of other dead cities, hardly ever explored as it seems. The ruins are lying deep below and far away on the slopes of distant hills. The Turkish border is very close here. Watchtowers and barbed wire fences mark this barren no man’s land. Somewhere on the other side lies the Turkish town of Antakya. In ancient times it was the metropolis Antioch on the Orontes. Saint Paul preached there for the followers of Jesus, the New Messiah, who were precisely in this town called Christians for the first time. The coastal area around Antakya was annexed by Turkey in 1939. Since then that new Turkish province has been known by the name of Hatay, but on Syrian maps the whole area is still indicated as a part of Syria.

Simeon the Stylite

The Kurdish driver of our minibus has jet-black hair and a pale face. He is constanly smoking cigarettes and he has a bad cough. But he knows the way quite well, he was born in the northern border region, which is mainly inhabited by Kurds.

Our first stop is the ruined monastery of Tel Ada, situated on a hill outside a large Kurdish village. Deir Tel Ada was founded at the end of the fourth century and later on several Syrian-Orthodox patriarchs, who started their career as pious monks, came from this place. Yoseph is leaning against the edge of two crumbling walls. He has visited the site several times, together with other Syrian-Orthodox people from Aleppo. ‘Our metropolitan loves this place,’ says Yoseph. ‘We tried more than once to clean it up a bit. All in vain. When we came back, it was even a bigger mess.’ He points at the Kurdish village below. ‘Stupid people!’ he says. ‘They keep ravaging the site, they cannot stand it that even the last trace of our Christian culture may be preserved.’

Much more evidence of that old Christian culture is found at Qala’at Samaan, devoted to the famous saint Simeon the Stylite. The site is built on the slope of a large hill and at the summit of it, offering a magnificent view on the widely undulating landscape below, the stone arches of four cross-shaped Christian basilica’s are standing consecutively one after the other.

Simeon the Stylite Sanctuary

A true Christian saint indeed! The gigantic church building, in those days the biggest on earth, was erected after his death in the year 490. Pilgrims from everywhere came to the holy site. They prayed in front of Simeon’s pillar, right in the middle of the main basilica, and they took small bits of it with them, as a kind of relic. So it happened that in the course of time only the base of the famous pillar is left. And also a stone lump with a sharp end, which looks like – forgive me, Dear Lord – a pinched off turd. The comparison is not far-fetched. When Simeon was still alive, his followers collected his excrement on the spot and sold it to the pious pilgrims. Holy shit! I cannot imagine that at any time a better hole in the market of true faith has been found…

A Taste of Barada

Our Kurdish driver is wandering around on Qala’at Samaan and keeps staring idly into space. He doesn’t fancy the remnants of this old Christian place of worship. When we drive back to Aleppo, he suddenly has a lot to tell. Yoseph, who knows a bit Kurdish, translates. His life in Syria is a mess, says our driver, and Kurds are treated like shit. He wants to emigrate to Europe, get a job there, start a new life and perhaps later on marry a decent Kurdish girl, brought over from his native area. He has it all figured out, so it seems. Yoseph starts arguing with him. Words are running high. And then it is all over. Our driver calms down, he keeps silent and starts coughing again. Yoseph explains: our man hasn’t got any higher education at all, his health is bad and he only speaks Kurdish. I must admit that Europe isn’t waiting to give him a warm welcome.

Barada Beer Damascus

We had to repeat our order several times, but finally the waiter comes back with two bottles of Syrian Barada-beer. It is a pale yellow liquid. It looks awful, and that is exactly how it tastes too. ‘Ditchwater,’ says Yoseph. ‘What else can you expect? It is brewed in Damascus.’ The river Barada flows through Damascus and it is the open sewer of the capital. ‘Nothing good comes from that place,’ says Yoseph once more. What can I say? We are in Aleppo. Damascus – that is where the bastards of Timur the Lame live.

It was the last time we sat together under the stars of a hot Syrian night and exchanged our views, our hopes and fears for the future. Two stones touching each other for a short time and then rolling apart again, pushed away by the force of coincidence. Or fate. A couple of years later I received a Christmas card from Yoseph. ‘I am now in Salzburg, Austria, to follow a German course,’ he wrote. ‘May the Lord Jesus Christ bless you and fulfil all your ambitions and wishes.’ He didn’t mention anything about studying at a British university, but his English was better than ever before. And though he was far away from his Syrian roots, he still knew how to use that modern world language to express the ancient Syrian-Orthodox message, his belief in the language of Christ.

Shlama, Yoseph, my companion to Syria’s almost forgotten interior. You were an excellent guide.

|

Homeland

Homeland  Syria

Syria  Aleppo

Aleppo

Homeland

Homeland  Syria

Syria  Aleppo

Aleppo